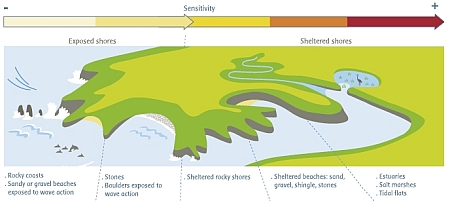

Impact des hydrocarbures sur différents types de côtes (en anglais)

Impact of Oil on Different Types of Coasts

When an oil spill reaches the shoreline, or occurs very near the coast, the phenomena of soiling and coating in oil can have an impact on the populations in the intertidal zone and the various human activities which take place by the sea. Marine birds and mammals are also obvious victims, such as numerous species of birds feeding on the foreshore at low tide and nesting on the seafront, or marine mammals resting on the shore. However, the algae, fish and shellfish which live in coastal pools, on the rocks and in the sand or mud, are inevitably affected.

Depending on the type of shoreline, the impact can range from being relatively limited to, at the other end of the spectrum, extremely dramatic. The sensitivity of different substrates to oil varies considerably, from rocky coasts to pebble beaches, gravel, coursegrain sand, fine-grain sand, marshland, coral reefs, and so on.

Rocky coasts

Exposed, steep rocky coasts provide an ideal surface to which large quantities of oil can stick. They are fairly quickly cleaned by the mechanical effect of subsequent wave action, and therefore suffer relatively little from oil spills.

Rocky outcrops, which may be submersed at high tide or in heavy swell, can be more severely affected, especially if the outcrop contains rock pools rich in flora and fauna, where thick layers of oil are likely to accumulate.

Beaches

Pebble, gravel and course-grain sand beaches are high risks areas in terms of profound contamination. Most hydrocarbons can easily enter gaps and flow so deep that it is practically impossible to remove them without seriously damaging the populations living within the sediment substrate.

Fine-grain sand beaches tend to retain oil on the surface, as the oil is most likely too viscous to penetrate into the depths through the fine spaces. Oil may accumulate along the high tide mark and be covered over with a layer of clean sand of varying thickness. Beach growth may cause layers of oil to be covered with sand, creating alternate layers. Buried oil is very problematic as the layers of oil may be uncovered by waves and swept away to then pollute other areas.

Mudflats and marshes

Intertidal marshland, including fish ponds, oyster pits and marshes, is particularly vulnerable. The networks of channels favour the transportation of oil towards very sheltered areas where low energy regimes and fine sediment retain them for long periods of time. Oil quickly and severely affects the populations of invertebrates living in the sediment, and the parts of plants in contact with the water. Human intervention in this type of site can lead to risks of disruption to the site and alteration of the ecological balance. Intervention in these areas should be well planned and carried out carefully.

Marine marshes in temperate areas, like tropical mangroves, are particularly sensitive to oil pollution. The respiration of the aerial roots of mangrove trees can be seriously impaired by even a thin lens of oil. Furthermore, numerous species live in these areas, some permanently, others on a seasonal basis, for many at the juvenile stage, when they are particularly vulnerable.

Oiling of a mangrove swamp during the season when young prawns feed there before heading out to sea can have serious consequences for coastal fishing and the biodiversity of the surrounding environment for several months, or even years.

Coral reefs

Coral reefs are protected by mucus secreted by their polyps and thus generally resist small, isolated accidents fairly well. In addition, a protective layer of water usually remains between the corals and the surface oil slick. However, repeated pollution incidents can have a serious impact on them, as can large-scale oiling of the surface layer of reefs (the only living part of the reef) caused by the tides and swell. Some of the many species of fish, invertebrates and marine algae which live in coral habitats can be severely impaired even if the coral itself has only suffered mildly.

Photo: NOAA